Written by Matthew O’Malley

“It is a riddle, wrapped inside a mystery, inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key.” -Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill (1874-1965), the heralded British Prime Minister from the mid-1900s used the above quote to describe Russian foreign policy during a portion of his era as Great Britain’s political leader. Interestingly, it is well documented that Winston Churchill was a person who stuttered.

Charles Van Riper (1905-1994), a stuttering research pioneer and contributing founder to the speech and language pathology field, was also a person who stuttered. Van Riper dedicated his life to improving treatment methodologies for stuttering and better understanding the nature of this puzzling condition.

It has been documented that Van Riper borrowed Churchill’s quote on foreign policy to describe the nature of stuttering. “It is a riddle, wrapped inside a mystery, inside an enigma.”

But perhaps there is a key…

The Dissociative Model & Hypothesis of Stuttering

According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), “Dissociation is a disconnection between a person’s thoughts, memories, feelings, actions or sense of who he or she is.” (2022)

In everyday vernacular, dissociation brings with it strong connotations and assumptions. It usually connotes ideas of mental health conditions. This is understandable as the term is used almost exclusively in the context of these conditions.

While there is truth in these connotations due to an array of psychiatric diagnoses that contain a dissociative element, the actual term dissociation is broad. Dissociative experiences are a part of the day to day lives of virtually every human being.

The APA continues on dissociation, “This is a normal process that everyone has experienced. Examples of mild, common dissociation include daydreaming, highway hypnosis or “getting lost” in a book or movie, all of which involve “losing touch” with awareness of one’s immediate surroundings.” (2022)

In summary, dissociation is experienced by everyone and is a spectrum. There are different levels of dissociation and a variety of unique dissociative states comprised of different subjective experiences.

On the opposite end of the spectrum of dissociation is experiencing the “here and now”.

As you will read in this article, it is asserted that in moments during and surrounding stuttering, the individual who stutters is often in a dissociative state. It is being asserted in this piece that this dissociative state is a significant causal and contributing factor to fluency disruption and stuttering. Remediation strategies for stuttering should focus on and/or include the elimination or reduction of the intensity and frequency of these dissociative states based on this dissociative model of stuttering.

Understanding this dissociative-state/trance, emerging from it, and observing your own waxing/waning in and out of the present moment into dissociative states throughout one’s day is important.

…perhaps, there is a key.

Trauma & Dissociation

I know, I know. We just finished up normalizing the term dissociation. Now, we’re going to talk about dissociation AND trauma in the same discussion?! Well, yes. Understanding the relationship between trauma and dissociation is an important component to this article, and while we’re normalizing terms, let’s normalize the term “trauma” as well.

Oxford Languages defines trauma as “a deeply distressing or disturbing experience” (2023). This definition allows for broad interpretation which is important. It is important because it doesn’t matter what the “event” or “experience” of “trauma” is/was. If the event is either “deeply distressing” and/or “deeply disturbing” it meets the criteria for trauma under this definition.

In other words, trauma doesn’t have to be what is traditionally thought of as trauma from a societal perspective. It doesn’t have to be an obvious experience of abuse, victimization, etc. It can include a experiences such as a rejection on the playground, a sibling making a remark, or a break-up with a 7th grade crush. It is more about how the “traumatized” individual experienced the event(s) internally.

In shedding light on the broadness of trauma, Dr. Rachel Yehuda of the Icahn School of Medicine Mt. Sinai states, “The most important message is really that we all experience trauma in our lives.” (Double Blind Magazine, 2022)

Also commenting on the nature of trauma, MD and trauma expert Gabor Mate’s views deal more with an individual’s response to a distressing or disturbing event. He states trauma “is not what happens to you, [but] what happens inside you as a result of what happens to you.” He goes on to say “much of what we call abnormality in this culture is actually normal responses…the abnormality does not reside in the pathology of the individuals, but in the very culture that drives people into suffering and dysfunction.” (Double Blind Magazine, 2022)

In putting all this together, “trauma” is experienced by everyone and affects us all to varying degrees on an internal level.

Speech as movement

If you’ve been following this website for a while, you likely know that I often state that speech is movement. For those who are new, let me recap.

For a person to speak, movement of the speech apparatus is required. Is this obvious? Yes, however, it is important in the context of this article to frame the stuttering condition in this way. This is because when a person who stutters goes to speak and begins to stutter, the intended speech movements are not happening. The person who stutters either “blocks” or “stutters”. In either case, the intended speech motor movements do not happen. Based on this logic, it is clear that somewhere along the way impeded speech movement is part of the stuttering condition.

Again, this may seem obvious. At the same time, people and organizations intending to unravel the stuttering condition look at stuttering from a variety of different vantage points. Some vantage points’ initial premises are debatable. For this article we are building off of a reasonably unquestionable assertion. That assertion, as stated is, “somewhere along the way impeded speech movement is part of the stuttering condition.”

Building off the bedrock of that assertion, the question becomes “Why?”

The relationship between stuttering, dissociation, trauma, and movement

Trauma and dissociation are intertwined. When a person experiences a trauma or foresees an impending trauma, it is the mind/body’s objective to protect itself. The mind’s response for this protection is sometimes a dissociative escape. In other words, the present moment reality is a significant threat or is painful, therefore I will dissociate to escape it. The resulting state-of-mind/body (SOMB) the individual experiences is a dissociative one to escape the traumatic reality. These types of dissociative states happen when the person experiencing a threat/danger/trauma is one they cannot physically resolve. In other words, they cannot fight the “threat” nor can they flee/”flight” from the threat to adequately remove the danger. In this predicament (when one cannot physically remove the threat), the mind dissociates as a last resort. In a way it is a “flight” response, but only in the mind. The mind “flees” the reality or impending threat by removing itself in some capacity from the situation. Again, I want to stress that a dissociative state does not mean a complete break from reality. It does not mean that a person has lost all touch with the world and themselves. It is simply a dissociative alteration in a person’s state-of-mind/body (SOMB) intended for protection/escape.

Research from the The National Institute of Health states, “There is a robust correlation between dissociative symptoms and exposure to trauma” (Boyer, S. M., Caplan, J. E., & Edwards, L. K., 2022). The article continues, “It is a human phenomenon, experienced by all to varying degrees on a continuum ranging from benign to problematic.” Adding more, the article states, “…dissociative experiences are often benign and under the individual’s control…On the other end of the continuum are trauma-related dissociative phenomena that, while adaptive in some ways, can become entrenched over time and impair overall functioning. In the face of overwhelming traumatic experience, dissociation can offer a psychic escape when there is no physical escape.” (Boyer et al., 2022)

In summary, when a person experiences trauma or foresees a powerful impending threat they cannot physically resolve, the mind’s response is often to dissociate.

Linking Stuttering to Trauma and Dissociation

I have written extensively in years past about stuttering and its relationship with trauma, fight/flight/freeze, ptsd, etc. As I am writing this article for established readers and those new to the site, I am attempting to reiterate important and necessary information required to understand this article as concisely as I can; then incorporating the new information and assertions. To partly accomplish this, below is a graphic from the Stuttering Forward page in 2019 that visually summarizes the continuous interplay between stuttering, trauma, ptsd, etc.

To add some language to the above image, there are a few contributing factors to address. The first one is how the human being is a deeply social animal with a need for connection with other human beings. The human being is utterly reliant on other human beings for their own survival. An infant and child relies on other human beings to cater to some of the most important needs for survival. These include food, water, and physical protection. If there is not another human being providing for these needs, that child will not survive. Therefore, the need for human attachment/connection is a survival need and is perceived as one in the dependent child. A perceived threat to this need (whether real or not) can be traumatic.

As an adult, the need for connection and attachment with others is also a survival need. For the majority of human beings’ history, we have lived in tribes and communities. To belong to a tribe/community and to establish/maintain one’s standing in these tribes/communities is/was a survival need. In pre-civilization, if an individual was ostracized or banned from their tribe/community, this was a significant threat to their survival. Surviving on one’s own in the wilderness is unlikely. Because of this, the human need for belonging has evolved to be deeply ingrained in our makeup throughout the lifespan. Any threat to the need for belonging is subconsciously or consciously perceived as a threat to one’s survival.

As a result, experiences of belonging and connection bring on states of tranquility and safety. Experiencing shame, ostracism, and/or humiliation is the opposite experience of connection/belonging. It is an experience of extreme disconnection with our fellow human beings and as a result brings on powerful states of disconnection and shame. These states are an alert that your mind is perceiving a high level risk to its own survival.

Peter Levine (MD), researcher and thought leader on trauma wrote a groundbreaking book in 1997 called “Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma”. In reading Dr. Levine’s book and some of his other research on trauma, he has a basic formula for what brings on trauma. In my understanding his formula is as follows:

(a perceived powerful threat) + (powerlessness/helplessness to stop it) = traumatic experience

Dr. Diane Poole Heller paraphrases Levine’s views on the website “Trauma Solutions” stating, “According to Peter Levine, the founder of Somatic Experiencing, trauma is experiencing fear in the face of helplessness. Fear plus helplessness equals trauma.” (2020)

Trauma, dissociation, and impaired motor ability (movement)

According to the International Society For The Study of Trauma and Dissociation, symptoms of dissociation include:

- feeling that someone or something else takes over

- Loss of senses such as…speech

- loss of feeling or movement in part of the body

- Involuntary movements or impulses that do not feel they are yours (ISSTD, n.d.)

The National Institute of Health adds, “Over time, and particularly in the context of repeated trauma during childhood, the use of dissociation can become a rigid and automatic response to stress that disrupts “the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behavior” (Boyer et. al, 2022).

Published in the European Journal of Psychotraumatology, is an article called “The Shutdown Dissociation Scale (Shut-D)”. Shut-D is a clinical evaluation scale which enables practitioners to assess the existence and severity of dissociative symptoms in a client. The Shut-D scale assesses a wide range of dissociative responses and attempts to give names to different types of dissociative responses. (Schalinski, I., Schauer, M., & Elbert, T., 2015)

Many of us have heard of the “fight or flight” response or even the “fight/flight/freeze” response. The Shut-D goes significantly further than these few categorizations of responses.

One such category is titled the “flag-faint-fright” response. The authors of the article state:

“Further stages of the defense repertoire include “flag–faint” with its dissociative properties. Maximal proximity of danger…is associated with more dissociative responding (Johnson, Pike, & Chard, 2001). It consists of functional sensory deafferentation, motor paralysis, alterations of the consciousness, and loss of speech… (Scaer, 2001). “Fright–flag–faint” becomes adaptive when there is no perceived possibility for flight-or-fight. Dissociative responding may be conditioned (Bolles & Fanselow, 1980). First, disruption of the ongoing perceptual or bodily experiences provides the basis for shutdown dissociation and interferes with an integrative representation of the environment and the self (Schauer & Elbert, 2010). It is likely that this ongoing disruption of integrative processes would play a key role in the development and maintenance of PTSD. Dissociative responding could then be understood, on the one hand, as an adaptation in order to survive during life-threat” (Schalinski, et. al, 2015)

Of the primary things we are looking at in these quotes from these well established institutions is how movement and speech can become impaired during a dissociative response. The research, language, and literature has strongly established that a component of a dissociative response often includes the impairment of motor skills (movement) and speech.

Establishing that people who stutter experience a dissociative response during interaction and moments of stuttering:

In 2000, an extremely useful piece of research (for the purposes of this piece) was conducted by speech-language pathologist Louise B. Heite titled “LA PETITE MORT: DISSOCIATION AND THE SUBJECTIVE EXPERIENCE OF STUTTERING”. The experience of dissociation in people who stutter was investigated. (Heite, 2000)

The study included 103 people who stutter. The study acquired collective descriptions of the experience of stuttering from the participants through a questionnaire. There were eight sections to the questionnaire which included narrative descriptions of stuttering moments, time & sensory perception (during stuttering moments), degree of perceived control, awareness of emotional, cognitive, and bodily states, etc.

In analyzing the questionnaires, 70 of the 103 participants reported an experience that aligns with a dissociative state during moments of stuttering. Dissociative elements across the participants included depersonalization (dissociative state where you feel like you are observing yourself), loss of touch with control of their bodies, a disturbance in their sense of time, and more. (Heite, 2000)

Ms. Heite states (2000):

“Many persons who stutter have reported that they experience a disturbance of their sensory perception or of awareness of self or surroundings during the moment of stuttering. In a description of this disruption experienced by a client, Van Riper used the term petite mort (“little death”). The term suggests both the completeness and the intensity of the experience (1982). Because this is a purely subjective experience, inaccessible to the outside observer except through the indirect means of inference from observable behaviors or through client self-report, the phenomenon has received little to no attention from researchers. However, the possibility of dissociation in connection with a stuttering event has implications both for fundamental understanding of stuttering, and for the choice of therapy approaches for particular individuals.”

She continues, “The narrative descriptions of the petite mort experience (dissociation (added)) reinforce the description derived from the check-box forms. Those who reported a petite mort experience described dissociative symptoms and a sense of isolation in their narratives.” Adding more she states, “Only those who reported petite mort experience also reported a disturbance to their sense of time. The presence of dissociation simultaneously with stuttering may have a serious effect on the course of therapy.” (Heite, 2000)

Synthesis and Insight

In referring back to the explanatory graphic of the stuttering cycle, we can begin to make sense of the link between dissociation and stuttering. As a person who stutters develops and begins interacting with different people in the world, there can be an adverse reaction (social traumas) to their stuttering. Even with a developing child with typical developmental disfluencies, there can be an adverse reaction. These adverse reactions (bullying, shaming, ignoring, ostracizing, punishing) from peers, family, and other relationships are perceived as a threat to one’s survival (threat to survival-dependent attachment needs). This repetitive cycle of social traumas continues to occur and “snowballs”.

At the heart of the struggle of stuttering is a lack of control; a helplessness due to one’s lack of self-agency over their ability to speak. The very nature of trauma is the presence of a significant threat combined with a helplessness to stop it. The experience of stuttering aligns precisely with this established model of trauma. The person who stutters enters an interaction and identifies a significant threat (ostracism, humiliation) based on past adverse reactions to their stuttering. The perceived avenue to prevent this threat is to speak without stuttering during the interaction. In attempting to resolve the threat (ostracism etc.), the person who stutters attempts to speak and experiences a helplessness to free themselves from a stuttering moment and even anticipates the possibility of the next stuttering moment upon “finding a way out” of the current stuttering moment. If this is not a repetitious and cyclical process of trauma by definition, I’m not sure what is.

Because these experiences continue to happen throughout a day, year, and lifespan, the cyclical trauma of stuttering continues and is reinforced as is the need to dissociate.

Based on what has been written throughout this article, it is a normal human response to enter a dissociative state during a traumatic event. Dissociation is a trauma response when an impending threat is detected and the person feeling the threat does not have physical means to deter it. The mind, as a result, resorts to a state of dissociation to escape the situation “mentally”. The person who stutters repeatedly experiences a threat of ostracism coupled with an inability to deter it. Because of this (impending threat + inability to stop it), the mind escapes inside itself through dissociation to protect itself from the looming trauma. The logic and research supports the idea that many people who stutter enter a form of dissociative state leading up to, during, and after stuttering moments.

While the dissociative escape is intended to protect the person who stutters from the pain of the moment in the present reality, it ends up further hurting the person who stutters. The entrance into the dissociative state is to escape the reality of what’s happening, however, the dissociative state experienced by the person who stutters results in further disarmament of the person’s volitional control over their speech. Despite the mind’s intentions to protect the person through dissociation, this cycle continues to feed itself as the dissociative state further contributes and/or causes the disarmament of the speech mechanism. As a result, the traumatic events that come with stuttering such as ostracism, embarrassment, and humiliation perpetuate even more due to the loss of agency over one’s speech in the dissociative state. This loss of agency increases the intensity and frequency of stuttering traumas. Because the intensity and frequency of these traumas increases, so does the minds’ perceived need to dissociate in speaking situations. This cycle continues to feed and reinforce itself which contributes to the persistent and chronic nature of the stuttering condition.

This article has made use of research demonstrating that dissociative states can and often do impair the motoric ability (movement) of the person who is in the dissociative state. Specifically, some dissociative states disarm a person’s ability to speak.

Are we seeing the connections?

It is the assertion of this article that dissociative states before, during, and after stuttering moments significantly contribute to causing the behavior of “stuttering” and “blocking”.

The subjective description of moments of stuttering and/or blocking from my own experience and from many people who stutter I have heard is described as a complete loss of control and inability to “get out of a stutter” and begin speaking again. The description of a person who stutters “coming out of a stutter” is similarly non-volitional. Coming out of a stutter or block is often described as “it just happened” or “the stuttering block just ended”. It is not described as something under a person’s voluntary control.

This is because the person stuttering is in a different state-of-mind/body (a dissociative one) during the stuttering moment. They are in a dissociative state and have literally lost voluntary control over their speech.

The dissociation that is attached to stuttering is like many other dissociative states. The person experiencing dissociative states often does not have control over when they go into them and when they come out of them. This mimics the experience of a block/stutter. I’m asserting that it mimics the involuntary entrance and exit of a dissociative state because the person stuttering is entering and exiting a dissociative state that is disarming their ability to speak. It mimics it because it is it.

I am not asserting in this that the complete cause of the onset of stuttering is dissociation, however, I am also not dismissing it. I do assert that dissociative states (and their waning) likely contribute to the “spontaneous recovery” of children who stutter or the maintenance of the stuttering condition (dissociative states persist and/or increase) in those who do not “spontaneously recover”. While that is not the focus of this article, I wanted to address it. I do assert that dissociative states are a significant contributing factor to causing stuttering moments, and how/why the stuttering condition waxes and wanes over time. Again, I am not making a claim that dissociation is the complete cause of stuttering. At the same time, I believe there is reasonable assertion to be made that it plays a significant role in onset and/or is the causal factor.

Dissociation can explain the plethora of mysteries and ameliorating conditions

- Virtually all people who stutter stop stuttering when speaking to a metronome. A metronome removes the dissociative state by providing stimuli to focus on in the present moment. This brings the person who stutters into the present moment and out of a dissociative state. Also, part of the dissociative state of stuttering is a distorted sense of time. The metronome provides environmental stimuli that orients the person who stutters to time. These factors “break” the dissociative state.

- There have been numerous research studies and trials to use pharmaceutical drugs to treat stuttering. While the hypothesis behind using these pharmaceuticals was a “dopamine hypothesis of stuttering”, the pharmaceuticals tested on people who stutter have primarily been drugs categorized as antipsychotics. The drugs do usually lower dopamine, however they are used to treat significant psychiatric conditions of dissociation. Studies have shown many of these pharmaceuticals decreased the participants’ stuttering. The efficacy of these drugs to treat stuttering is likely due to their anti-dissociating effects. The person who stutters takes these compounds and it lowers the person who stutter’s dissociative experiences resulting in less stuttering.

- Depersonalization is a form of dissociation. Depersonalized states are likely a significant part of the dissociation experience during stuttering moments. The term was not used extensively due to different terms resulting in reader confusion.

- A distorted sense of time is often part of a dissociative state. The lack of orientation to time in a dissociative state could serve to explain one’s loss of control of speech motor ability. A prerequisite for motor planning is orientation to time.

- Secondary behaviors of stuttering (foot tap, other bodily movements) were useful early on in their use to “break the dissociation” as it brought a person’s attention to stimuli in the “here and now” (some of the people who stutter’s focus was on the secondary movement). It’s effects faded as the secondary behavior became “normalized”. This can also serve to explain why delayed auditory feedback often has a stutter-diminishing effect when first using it, however, its efficacy fades over time.

- The predisposition to stuttering may be a predisposition to a dissociative state.

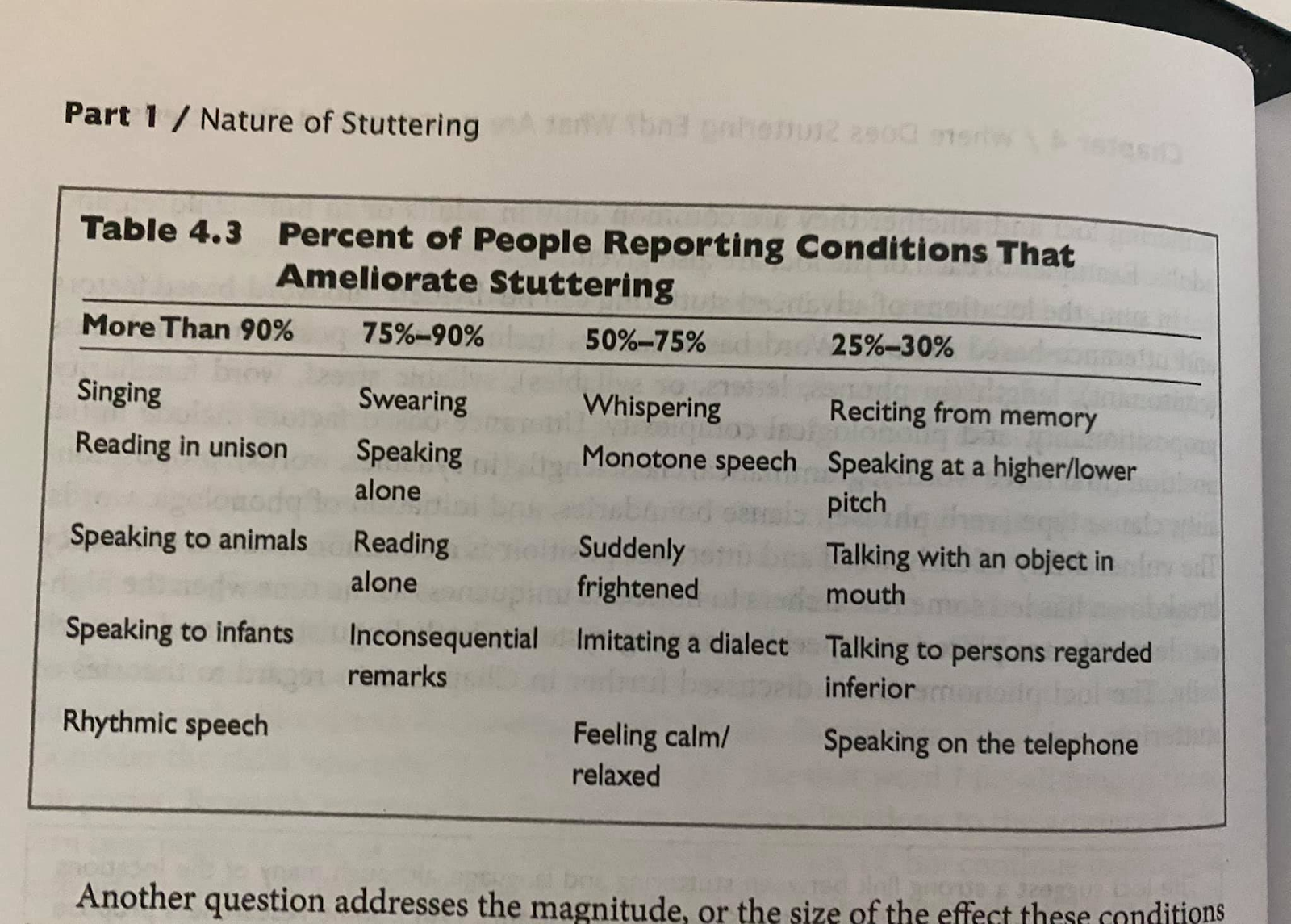

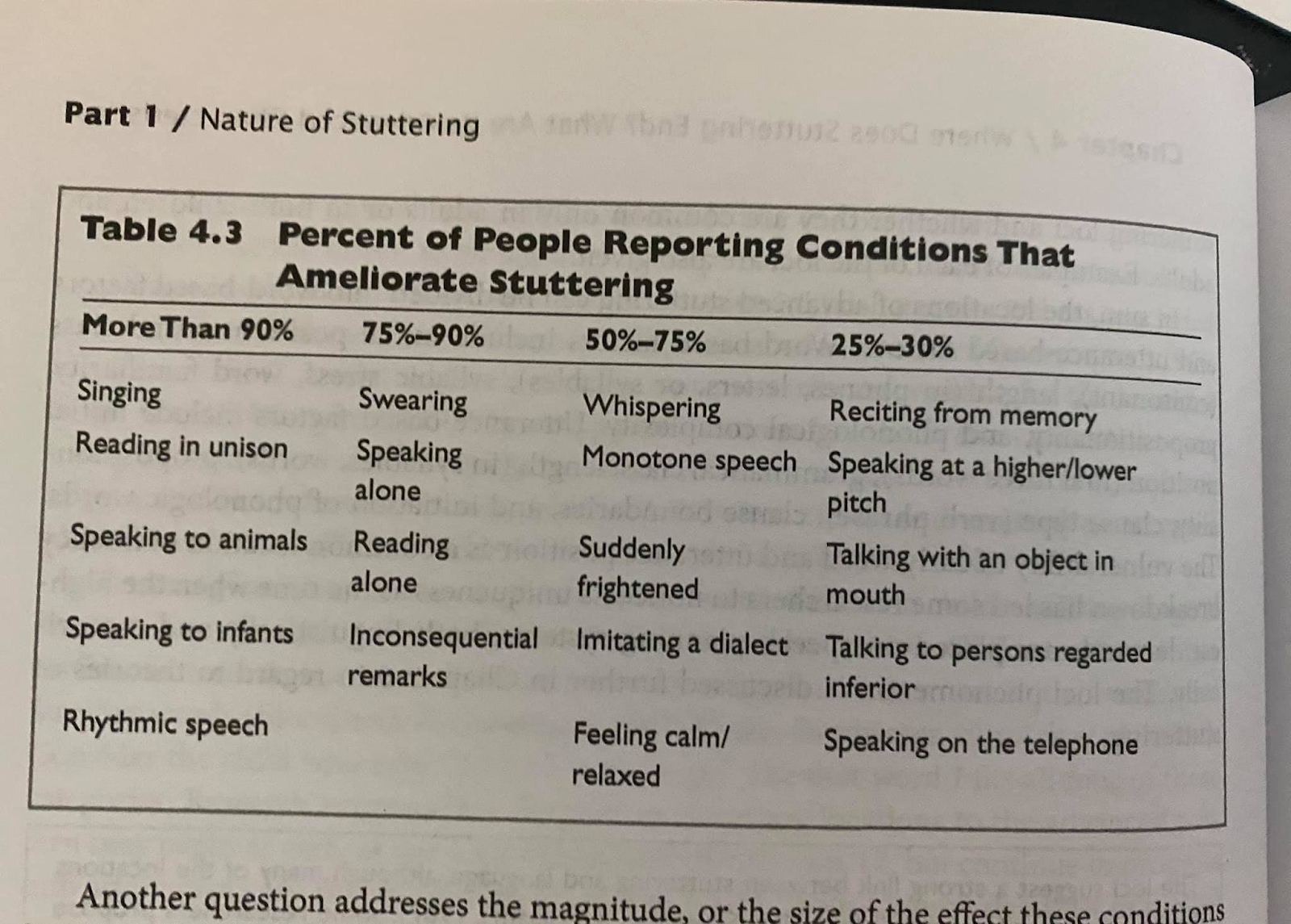

(Manning, W. H., & Dilollo, A., 2018)

(Manning, W. H., & Dilollo, A., 2018)

(Manning, W. H., & Dilollo, A., 2018)

The Dissociative model of stuttering has the ability to credibly explain each one of the ameliorating conditions of stuttering (shown below). States of “non-self” (speaking differently than the “true self” would), focusing on stimuli “in the now”, lack of attachment consequences (therefore no need for the mind to expect trauma and respond with dissociation), different states-of-mind-body (anger for example), are all credible ways for the dissociative model of stuttering to explain the ameliorating conditions of stuttering along with other puzzling phenomena about stuttering.

“Perhaps there is a key.” -Winston Churchill

References

Bolles, R. C., & Fanselow, M. S. (1980). A perceptual-defensive-recuperative model of fear and pain. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(2), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x0000491x

Boyer, S. M., Caplan, J. E., & Edwards, L. K. (2022). Trauma-Related Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders: Delaware Journal of Public Health, 8(2), 78–84. https://doi.org/10.32481/djph.2022.05.010

Fact Sheet III – Trauma Related Dissociation: An Introduction. (n.d.). ISSTD. https://www.isst-d.org/public-resources-home/fact-sheet-iii-trauma-related-dissociation-an-introduction/

Heite, L. (2000). La Petite Mort: Dissociation and the Subjective Experience of Stuttering. https://ahn.mnsu.edu/services-and-centers/center-for-communication-sciences-and-disorders/services/stuttering/professional-education/convention-materials/archive-of-online-conferences/isad2001/la-petite-mort-dissociation-and-the-subjective-experience-of-stuttering/#:~:text=The%20presence%20of%20dissociation%20simultaneously,learned%20in%20classic%20stuttering%20therapy.

Heller, D. (n.d.). Types of Trauma and Identifying the Signs – Trauma Solutions. https://Dianepooleheller.com/. https://dianepooleheller.com/touching-on-trauma/

Johnson, D. M., Pike, J. L., & Chard, K. M. (2001). Factors predicting PTSD, depression, and dissociative severity in female treatment-seeking childhood sexual abuse survivors☆, ☆☆, ★21☆☆ The data from this article is part of a larger treatment outcome study on cognitive processing therapy for sexual abuse.22★ Assessments and therapy sessions were conducted at the Center for Traumatic Stress Research at the University of Kentucky. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25(1), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00225-8

Manning, W. H., & Dilollo, A. (2018). Clinical decision making in fluency disorders (4TH ed.). Plural Publishing, Inc.

Margolin, M. (2022, May 26). Trauma is the New Buzzword, but Does Everyone Really Have It? DoubleBlind Mag. https://doubleblindmag.com/defining-trauma/

Scaer, R. C. (2001). The neurophysiology of dissociation and chronic disease. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 26(1), 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009571806136

Schalinski, I., Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2015). The Shutdown Dissociation Scale (Shut-D). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 25652. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v6.25652ri

Hello Matthew:

I like your linking stuttering with dissociation and trauma. I have come to very similar conclusions in recent years and have determined in my own study and exploration of the phenomenon of stuttering that it certainly has a strong sympathetic nervous system component. I observe avoidance and or dissociative responses in the moment of stuttering as central in understanding the fuel and fire of debilitating stuttering.

Along with brain plasticity—conditioned circuitry assigned to the fight-flight-of freeze response, and the frequency therein—strongly conditioned; aberrant speech motor learning, and the development of a hierarchy of escape/defense/secondary physical concomitants

makes the condition an enigma to just about everyone—especially we stutterers.

It is worth exploring further. Something I have found very descriptive and helpful are scales describing degrees of trauma symptomology; the shut done scale is new to me, thank you for posting.

You might want to look at Polyvagal Theory. I find it a very good fit for stuttering, A lot of useful information regarding dorsal vagus nerve pathways and the trauma response. It envelopes dissociation implicitly.

Speech Pathology is finally embracing other disciplines in researching stuttering, especially explaining the neuro-development of stuttering and why some children do and do not out grow stuttering.

I have always thought that stuttering demands a multidisciplinary approach because of its complexity, and the need for great attention toward the well being of individuals living with the disorder. It is a serious condition with immense impact affecting pws.

So few who want to treat stuttering and fewer who have a fair to good understanding of stuttering.

The future in alleviating a lot of the suffering, and diminishing its impact, if not eliminating stuttering, I believe lies with out-of-the-box thinking.

Jim

LikeLike

Congratulations Matt for this new article. As Jim said, when talking about stuttering, we should definitively look outside the box.

LikeLike